Frequently Asked Questions

What nationalities were represented in the Titanic’s crew?

While the majority of the crew were British (primarily English and Irish), it was a surprisingly international group. The crew included individuals from over 20 different countries. The most significant non-British contingent was the Italian and French staff of the À la Carte Restaurant. There were also crew members from Scandinavia, Germany, the Netherlands, Switzerland, Spain, China, and several other nations, reflecting the global nature of maritime labor in the early 20th century.

How did the Titanic disaster change international maritime laws for workers?

The disaster exposed fatal flaws in existing safety regulations, which had a direct impact on working conditions. The subsequent SOLAS convention created universal standards that benefited crew members immensely. Mandatory lifeboat drills ensured that crews were better prepared for emergencies. The requirement for a 24-hour radio watch increased the chances of a swift rescue, and the International Ice Patrol made their working environment in the North Atlantic significantly safer. While not explicitly labor laws, these safety reforms were a monumental step forward in protecting the lives of seafarers worldwide.

What was the role of the “Black Gang” (engineers and firemen) during the sinking?

The “Black Gang” played a heroic and vital role. As the ship took on water, the engineers, firemen, and trimmers worked tirelessly in the boiler rooms to keep the steam-powered electrical generators running. Their efforts kept the ship’s lights on, which prevented mass panic and allowed for a more orderly (though still flawed) evacuation on the upper decks. It also powered the Marconi wireless, enabling the distress signals to be sent. They essentially sacrificed themselves, as none of the engineers survived, to give others a chance of survival.

Were there non-European crew members on the Titanic?

Yes. The most well-documented non-European crew members were eight Chinese sailors working as firemen in the engine rooms. Six of them managed to survive. There were also a handful of other crew members from outside Europe, including a Japanese man working as a steward and several individuals from British colonies. Their presence underscores the global reach of the British merchant marine. For further context on artifacts and stories from around the globe, resources like the British Museum offer a broad perspective on global cultures.

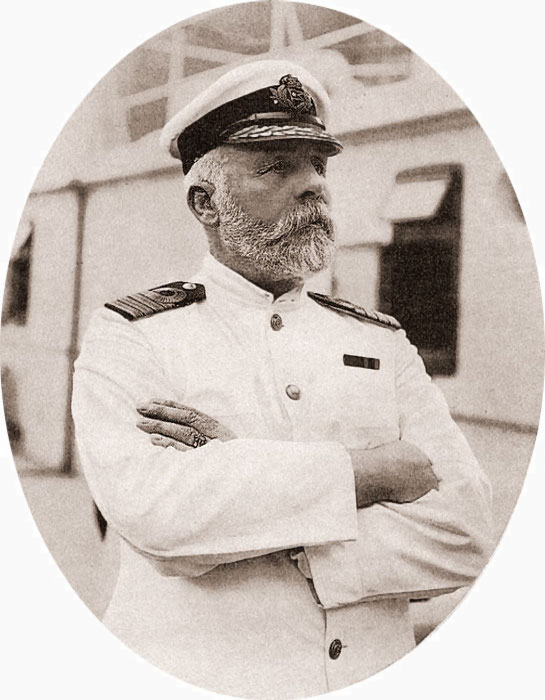

How did the class structure on land translate to the crew’s hierarchy on the ship?

The ship’s crew was a rigid reflection of the Edwardian class system. The officers, who came from middle-class backgrounds and had formal training, were at the top. Below them were the skilled tradesmen like carpenters and clerks. The vast majority, including able seamen, firemen, and most stewards, were from the working class. This hierarchy dictated pay, living quarters (officers had private cabins while firemen slept in large dormitories), and even chances of survival. Officers on the boat deck had the best access to lifeboats, while those working in the lower decks, like many stewards and the “Black Gang,” had the slimmest chance of escape.

For more detailed historical records and manuscripts, the British Library holds extensive collections related to maritime history. University history departments also provide excellent online resources for deeper research.

Disclaimer: This article provides a summary for informational purposes and reflects current historical scholarship. World history is vast and complex, and we encourage deeper study from academic sources.