Do you know that Queen Elizabeth II’s art curator was a Soviet spy?

Cold War Moscow was unlike any other place in the world. The KGB, the ever-present eyes and ears of the dreaded Soviet secret police, was everywhere. The only place that you could call safe, one political prisoner would later write in his book, was in your dreams.

At that time, the Russian capital was a place where death and life existed side by side, as did imprisonment and opportunity. To betray the state meant risking everything, yet that was precisely the choice some people made.

From a CIA counterintelligence officer to a British member of Parliament, meet some of the Cold War spies who risked everything, including their lives, to gain information.

1. Julius and Ethel Rosenberg

Married in 1939, Julius and Ethel Rosenberg were American communists who allegedly were the head of a spy ring that provided military secrets to the Soviets during the Cold War. The whole thing started sometime after 1940, when Julius took a civilian job in the US Army Signal Corps (USASC).

However, in 1945, the military learned of his communist leanings, so they fired him. But before that, Julius made sure to gain access to secret information with the help of Ethel’s brother, who was an Army machinist working on the Manhattan Project. This way, Julius got hold of handwritten sketches and notes pertaining to the atomic bomb.

Meanwhile, the Rosenbergs recruited others to deliver thousands of pages of documents detailing new aircraft and radar technologies. In 1950, both Julius and Ethel Rosenberg were arrested, and there was a trial too. Ethel’s brother testified against them, and they were found guilty of committing espionage.

President Dwight D. Eisenhower refused to grant them clemency, so on June 19, 1953, both of them were sent to death by electric chair at New York State’s Sing Sing prison, becoming the first American citizens to be executed for espionage.

Despite worldwide protests over the Rosenbergs’ treatment — many people believed that they had been victims of McCarthy-era red-baiting — the decoded messages released by the post-Soviet proved that Julius was, in fact, a spy during the Cold War. The evidence against Ethels is less conclusive, and her guilt is still being debated.

Here‘s a book that thoroughly tells the story of the Rosenberg case.

2. Klaus Fuchs

After Hitler came to power in 1933, Klaus Fuchs left his native Germany to study in the United Kingdom, where he got a doctorate in physics and eventually became a British citizen.

Despite his known communist sympathies, he was invited to work on Britain’s clandestine atomic bomb development program. As a result, at some point during World War II, he was sent to the US to join the Manhattan Project.

In the early years of the Cold War, Fuchs returned to England where he got a prestigious position at a nuclear energy research center. However, in 1950, he was arrested after US agents discovered that for several years he had been passing information to the Soviets, who by now had developed their own atomic bomb.

Fuchs confessed, openly stating that he “had absolute confidence in the Soviet policy” and that “the Western Allies purposely allowed Germany and Russia to fight to the death”. Despite the fact that Fuchs claimed not to know the true name of his American contact, the FBI followed a trail back to the Rosenberg spy ring.

And that led to the arrest of several conspirators, including the Rosenbergs. Fuchs, as opposed to Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, got off easy. After spending nine years in a British prison, he managed to immigrate to East Germany, where he resumed his physics career until his retirement in 1979.

Fuchs, who received the Karl Marx Medal, East Germany’s most important civilian honor, died in 1988, three years before the end of the Cold War.

3. Ray Mawby

Ray Mawby was a former electrician who served in the House of Commons during the Cold War defending so-called British values (he conducted a campaign, for instance, against the legalization of homosexuality).

Hatred of communism was basically a requirement for Conservative Party members like him. Yet in 2012, two decades after his death, a BBC reporter brought to light a file revealing that Mawby had been a spy for Czechoslovakia, part of the Soviet bloc during the Cold War.

Hundreds of pages of documents showed that Mawby, code-named Laval, began secretly passing on information shortly after Czech agents approached him at a cocktail party held in November 1960. Lacking access to sensitive information, Mawby provided them with political gossip, such as the existence of a secret investigation into a Conservative Party colleague.

He also allegedly supplied floor plans of the prime minister’s parliamentary office, as well as information about the prime minister’s security team. Mawby received £100 for each valuable tidbit, money he would spend on gambling and drinking habits, according to his handlers.

Later on, the Czechs increased the total to £400 per year. Though Mawby used to meet with his handlers several times a month, their partnership appears to have ended in 1971.

Surprisingly or not, there are also other Labour Party politicians who were Czechoslovakia’s alleged spies.

4. The Cambridge Five

Skeptical that a Conservative member of Parliament could ever be a spy for the Soviet Union, the British authorities were also taken aback by the upper-class backgrounds and elite educations of the so-called Cambridge Five, who turned to communism during their time at Cambridge University in the 1930s.

Young, wealthy, and privileged Britons becoming part of the Soviet sphere; spies infiltrating the government and handing over information to the communists; nuclear weapons; news correspondents with hidden agendas; scandals that badly affected Britain’s role in the Cold War and nearly wrecked the special relationship with the US.

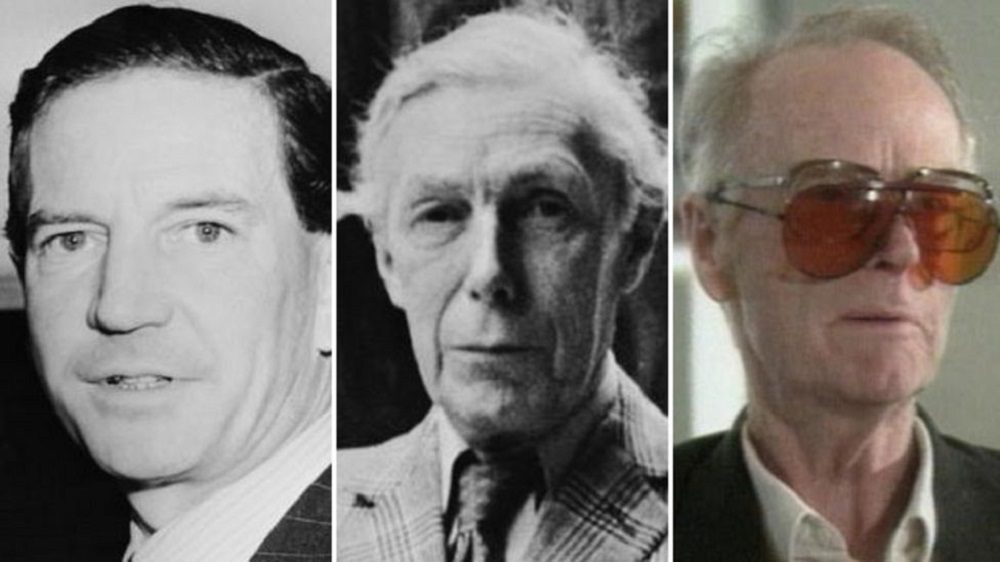

Although this may seem like the plot of any spy movie, it all happened in Britain in the 1960s. Within a decade or so after graduation, Anthony Blunt, Kim Philby, Donald Maclean, John Cairncross, and Guy Burgess all worked their way up to prestigious intelligence posts, which they used to share several secrets with the Soviets in the lead-up to and during the early years of the Cold War.

For instance, thanks to these double agents, who were supposedly motivated by ideology rather than money, the URSS found out about an Allied strategy to send anti-Soviet insurgents into Albania, as well as an Allied military plan of action during the Korean War.

When Philby, who ironically supervised the anti-communist section of MI6 (the British equivalent of the CIA), discovered that the authorities were closing in, he tipped off Burgess and Maclean, prompting them to defect to Moscow in 1951. In 1963, Philby joined them there, while Cairncross ended up in France and Italy.

Blunt, who was also Queen Elizabeth II’s art curator, confessed in exchange for immunity and was allowed to remain in Britain. None of the five were ever charged with espionage.

Keep reading to find out about another two Cold War spies!

5. Aldrich Ames

Wisconsin-born Aldrich Ames also betrayed his country and sold secrets to the communists during the Cold War period. Son of a CIA analyst, he wasted no time in joining the agency himself, beginning as a part-time clerical worker and eventually becoming a full-fledged spy.

Posted to places like Mexico and Turkey, Ames spent many years of his three-decade-long career trying to make Soviet officials infiltrate the CIA’s service.

Despite poor performance reviews and an obvious alcohol use disorder, he rose to become head of the counterintelligence program of the CIA’s Soviet division. Nevertheless, in 1985, while going through a financially catastrophic divorce, Ames achieved a position at the Soviet embassy in Washington, D.C., and offered to sell US secrets.

He was paid $2.7 million over the next nine years in exchange for leaving classified documents at prearranged drop spots for the KGB to pick up later. Furthermore, he disclosed the identities of nearly every secret agent operating for the Americans within the Soviet Union. As a result, at least 10 of these agents were subsequently executed.

Here’s what the CIA’s director stated later: “They died because this murdering, warped traitor wanted a Jaguar and a bigger house.” Despite the fact that US officials had suspected the existence of a communist spy for quite some time, Ames managed to avoid arrest until 1994, when the Cold War was already part of the past.

The FBI finally closed this case after discovering incriminating evidence on his computer and in his trash. Ames is currently serving a life sentence at a federal prison in Indiana.

6. Adolf Tolkachev

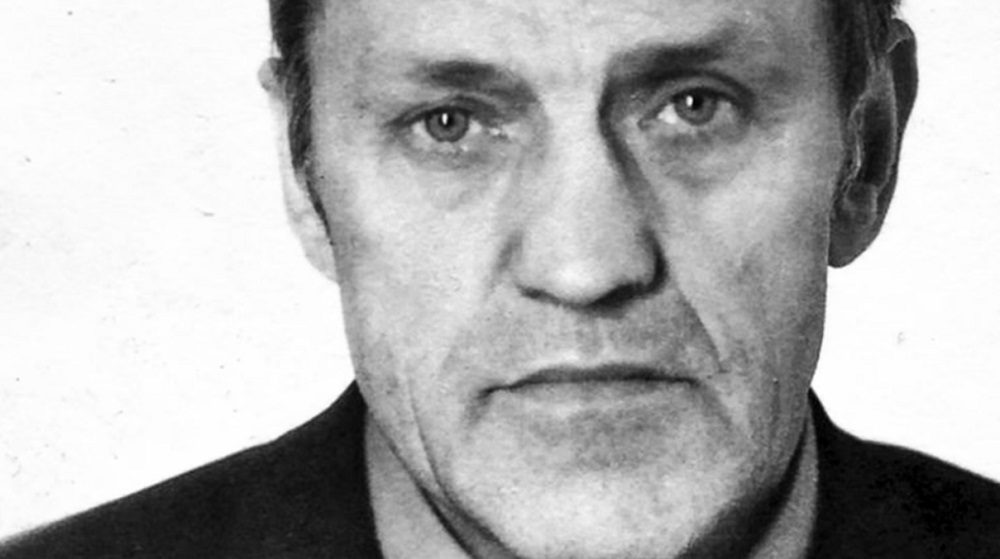

Despite the previous five examples, not every Cold War spy embraced the communist cause. In early 1977, for instance, Soviet electronics engineer Adolf Tolkachev started dropping notes into the cars of US diplomats, soliciting to meet with an American official.

The CIA initially ignored him, concerned that it would fall into a Soviet trap. But Tolkachev, who served in a military aviation institute in Moscow, kept insisting and eventually gained the CIA’s trust, collaborating with Americans for six years during the Cold War, from 1979 to 1985.

During all those years, he stuffed classified documents into his coat to photograph them at home with a CIA-supplied camera. While taking great precautions to avoid KGB surveillance, his CIA handlers would intermittently pick up this film, as well as handwritten messages.

Tolkachev was the one who let the CIA know that US bomber planes and cruise missiles could fly under Soviet radar. They also learned a lot about new Soviet weapon systems, saving the US military an average of $2 billion in manufacturing and research costs.

For his spy work during the Cold War, the CIA paid Tolkachev more than $1 million, though a great part of this amount was held in escrow in case he was planning a defection. The CIA even supplied Tolkachev with The Beatles, Led Zeppelin, and other Western rock albums for his son.

Nonetheless, he appears to have been driven more by revenge than financial gain, telling his CIA handlers about the imprisonment of his wife’s father and the murder of her mother during Stalin’s purges of the 1930s.

The collaboration ended abruptly before the end of the Cold War when it’s thought that former CIA agent Edward Lee Howard, and probably Aldrich Ames as well, notified the Soviets about Tolkachev’s activities. As a result, in 1986, he was executed.

Besides Cold War, you may also be interested in World War II: 10 Myths You Need to Stop Believing.